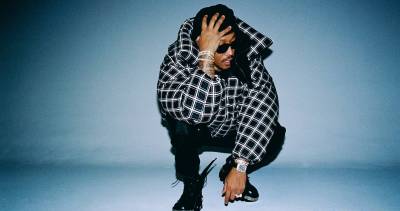

Harold Rhenisch

Despite its countless other virtues, the B.C. Interior has never been a hotbed of Shakespearean scholarship. This makes Free Will (Ronsdale Press, $14.95), the new poetry collection by Harold Rhenisch, all the more wonderfully improbable.

Okay, scholarship isn't the right word. Rhenisch writes about performing Shakespeare and reading Shakespeare, then picks up where some of the original texts end. Shakespeare, you'll remember, wrote 154 sonnets. Rhenisch continues the sequence, beginning with No. 155, using modern language and contemporary situations to underscore the famous timelessness of Shakespeare's themes and insights. Next year, another small independent publisher, Wolsak & Wynn, will publish an entire book of these (what to call them? neo-Shakespearean? post-Elizabethan? Elizabethan the Second?) sonnets, under the title Living Will.

Except for the fact that he once played Puck in an amateur production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, there's little in Rhenisch's CV that would predict such work, which he first thought of in the mid-1980s. The major breakthrough came "about eight years ago, at a writing course I teach. I was trying to get the students to understand how to use the language we use today and make it new. 'Here's a Shakespearean sonnet,' I said. 'Let's rip it apart.' " Still, for readers of CanLit, Free Will comes as a surprise because Rhenisch has been known for prose and poetry about family life and about the Interior as a bioregion.

His mother came to Canada as a child in 1929 with her father, a German Communist who had rioted against the Nazi Party in a part of Eastern Germany that's now in Poland. "He was one of the many Communists who came out to the Okanagan in the 1920s and '30s to start a utopian community, which failed. Then [with the Second World War], immigration was cut off for a decade, so they survived in isolation." Rhenisch's father, Johannes, lived through the Nazi period in Germany and immigrated to B.C. in 1952. Harold was born in 1958. His parents ran an orchard and he did too until a dozen years ago.

"I was fed up with what happened to the Okanagan," he says. "It became a diminished version of itself." In small-"c" cultural terms, he believes the Interior has suffered from the provincial equivalent of globalization. "Smithers, Vanderhoof, Burns Lake, Quesnel, Williams Lake--they're all pretty much the same now," he says. In his view, only 100 Mile House can lay claim to "a certain artistic atmosphere. It's really a cohesive community." He attributes this to the presence there, the past 70 years or so, of the Emissaries of Divine Light, a fringe religious group that had 1,000 members as recently as 20 years ago. But he lives at 150 Mile, not 100 Mile.

In 1992, his wife was hired as a school principal there. This means that, aside from a little teaching in Williams Lake, Rhenisch is free to write full-time. He once thought he could live on his literary income "if I published more and got more publicity. But I found that the more I made, the more expenses I had. Either way, I seem always to lose about $2,000 a year. Which is fine."

Comments