Understanding the narwhal: on watch

Last summer, Vancouver-based writer and photographer Isabelle Groc travelled to Baffin Island in Nunavut, to track narwhals, one of the most elusive species in the world. She joined a two-week narwhal research expedition, and reports on her Arctic journey and close encounters with the "sea unicorn".

This article is the fifth in a 10-part series. Read part four here.

Not long after we set up camp at Tremblay Sound, I faced my first night shift from 3:00 a.m. to 6:00 a.m. Being on watch was a big responsibility. While other team members were sleeping, I constantly kept an eye out for polar bears with my shift partner, Sandie Black.

Even though it was cold, rainy, and windy, neither of us stayed in the warm kitchen tent for more than 10 minutes at a time. I was glad I brought hand and feet warmers. I was initially worried about being able to stay awake throughout my shift, but Sandie, who had already been on several of these research expeditions, knew how to reinvigorate the spirits of a French woman with a sweet tooth. She unexpectedly prepared delicious crepes at 4:00 a.m. It worked, and with renewed energy, I was able to finish my shift.

It turned out that in addition to Sandie’s crepes, there were a few more surprises to enjoy before the end of the shift.

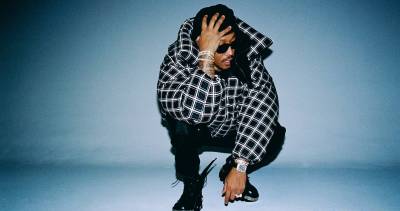

I was lucky to witness the most beautiful sunrise on the Sound I had ever seen, and as I kept myself busy taking photographs of everything around our camp, I noticed a beautiful translucent bird’s feather on the beach. I approached to photograph the unusual interplay of light and shadow, and was surprised to see an Arctic fox staring at me only a few feet away. That was the first of many encounters with several Arctic foxes that had made their way to our camp looking for scraps to eat. The foxes somehow became our camp companions, and we even started giving them names. In between whales, I enjoyed watching and photographing their playful behaviours for hours.

Only one day after we caught our first narwhal, we captured a second one; this time, a male about 3.5 metres long with a small tusk. Things were going well, and there was hope that we would capture seven more narwhals to tag them with the remaining satellite transmitters we carried. But the weather forced us to change our plans.

A strong easterly wind blew into our camp, bringing in icy rain. The team decided to pull the narwhal nets in, as it would be rough and unsafe to try and tow a whale to shore if we caught one.

That evening, a storm came full force. We secured any loose objects as best as we could and retreated into our tents, waiting for the storm to pass.

I couldn’t sleep that night. The wind was blowing so relentlessly that I thought my tent would fly away any minute. It didn’t, but the gale did rip another tent. By the morning, it was all over, and we awoke to discover snow behind the camp. I had survived my first Arctic storm and not too long after, we were ready to put the nets back in the water.

We were on watch again, waiting for the whales. That was our main activity, and we often saw hundreds of narwhals swim past the nets without ever getting caught. As we spent days waiting for a whale to come and get entangled in what looked like a hanging curtain, I realized how unpredictable, challenging, and sometimes nerve-racking this research project was for the scientists involved.

Most narwhals simply avoided the nets, and sometimes it just seemed pure luck that we caught a whale. Later on, we caught a male at 5:00 a.m., and Cortney Watt, a PhD student from the University of Manitoba who was on shift that morning, commented that the narwhal was moving very slowly at the surface when he hit the net. “He slept into the net,” she said.

Because narwhals were often caught in the middle of the night, we always were on the edge and slept with one eye open, ready to spring into action as soon as we heard the “Whale in the net” call.

When the narwhals were not around, polar bears served as a diversion that brought excitement to the camp.

One night, a female polar bear with two cubs walked along the beach by our tents. They went to the water, started swimming out, and approached the narwhal net. The mother stopped for a moment, turned back to her cubs, as if she telling them to wait while she investigated the situation, and then called for them to follow. “That was good mothering skills,” commented Jack Orr, who witnessed the event.

Another time, a polar bear moved closer and closer towards our camp.

The tension and excitement built as some of the team members, including myself, had never seen a polar bear before. Jack Orr and James Simonee, the Inuit captain, firmly walked towards the bear, fired a shot, and loudly said “get out of here.” The bear quickly left, and our camp routine resumed.

Comments

1 Comments

Anti-Narwhalism Umbrage Society

Jun 17, 2013 at 5:12pm

As that picture is an arctic fox, we at ANUS must protest your negligent, pro-fox, anti-narwhal leanings clear from your editorial illustration!