Homeless in Vancouver: First major look at B.C. homeless deaths disappoints

The Vancouver street magazine Megaphone issued a report on November 6 showing that homelessness nearly cuts a British Columbian’s life expectancy in half.

The Megaphone report, called “Dying on the Streets: Homeless Deaths in British Columbia”, uses B.C. coroner statistics to contrast the short lives of homeless people with the longer lives that the rest of the B.C. population can expect.

The report’s authors, Sean Condon and Jenn McDemid, get right to their point:

“As the data in ‘Dying in the Streets’ shows, the median age of death for a homeless person in the province is between 40 and 49. This is almost half the life expectancy for the average British Columbian, which is 82.65 years.”

So they say.

I know that living on the street can be a challenge and it can be dangerous but after a decade of being homeless, I say that there’s nothing intrinsically dangerous about living outside.

What’s dangerous about homelessness and potentially life-shortening isn’t homelessness itself but rather the “culture” of drugs and addiction that surrounds street life.

And the skimpy data that Condon and McDermid draw on proves my point as much as it proves theirs.

Homeless by the numbers

On the one hand, it’s important to credit the authors with attempting a popular analysis of homeless deaths in B.C. in order to come to useful conclusions.

On the other hand, “Dying on the Streets” reads like an attempt to find convincing statistics to back up the authors’ foregone conclusion that homelessness kills.

The executive summary begins by telling readers that at least 281 homeless people died in British Columbia between 2006 and 2013.

The authors then actually question the accuracy of the statistics they cite, saying that the true number of homeless deaths is likely much higher.

It's an important secondary theme running through the report—the lack of hard data and the need to keep better records on the deaths of homeless people; not just in British Columbia but across Canada.

In fact, this report, thin as it is on facts, could probably only be done in British Columbia, thanks to the diligence of the B.C. Coroners Service, which even made additional 2012-13 data available to the report’s authors.

All the hard numbers in the report are based on the findings of two B.C. Coroners Service reports: Deaths among Homeless Individuals. 2006-2007 and Deaths among Homeless Individuals. 2007-2013.

The B.C. Coroners Service prefaces the 2006-2007 report by explaining that it uses the same definition of “homeless” used by the Greater Vancouver (now Metro Vancouver) Homeless Count. The B.C. Coroners Service considers someone homeless…

“…if they were known to be living ‘rough’ or on the street (street homelessness), or were in an emergency shelter or being provided temporary shelter by friends or family (less than 30 days; sheltered homeless).”

The authors of “Dying on the Streets” say the definition is too narrow to give an accurate picture.

“Counting someone as homeless only if they are without housing at the exact moment of their death does not properly reflect the realities of homelessness in British Columbia.”

Perhaps not, but the hard numbers provided by the B.C. Coroners Service are at least based on reality.

I really have to quibble with Condon and McDermid’s willingness to cling to the slim reed of “average life expectancy” in order to make their only point sensational and newsworthy.

Average life expectancy is not, as I understand it, synonymous with actual age of death. The later is a record of what has really happened while the former is merely a prediction, or educated guess about what might happen.

The Megaphone report takes its average life expectancy figure from a B.C. Stats document called Life Expectancy at Age 0. The “82.65” is the average for “2013” between men (80.71) and naturally longer-lived women (84.55).

The authors appear to take the “2013” to mean that the average life span of British Columbians in 2013 is 82.63.

Please someone correct me if I’m wrong but I read the “2013” as a person’s birth date—that a person born in 2013 can expect to live 82.63 years.

I’m under the impression that the concept of life expectancy is conditional on a person’s birth date. Or as the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare explains life expectancy:

“In Australia, a boy born in 2010–2012 can expect to live to the age of 79.9 years and a girl would be expected to live to 84.3 years compared to 55.2 and 58.8 years in 1901–1910 respectively.”

Sounds trivial but it means that if our median homeless person died last year at, say, age 48, their life expectancy was considerably less than 82.63 years.

Their death age properly contrasts with the life expectancy of a British Columbian born when they were—50 years ago. And the life expectancy for a British Columbian born in 1965 was 72.17 years—more than 10 years less than the average cited by the Megaphone report and close to 68 percent of the predicted 1965 average.

No media outlet, so far as I have noticed, has questioned the report’s use (or misuse) of statistics. The report’s contention too perfectly fits the preconceived notion of homeless people living short, brutish lives.

Again, I have to strongly disagree that homelessness is intrinsically harmful. What’s actually harmful about being homeless isn’t living outside. That’s actually a pretty healthy environment.

What’s unhealthy and life-shortening about homelessness is the poisonous haze of drugs and addiction that surrounds living on the street.

The authors of “Dying on the Streets” can completely ignore the fact but they can’t hide the glaring evidence in the statistics they cite.

Homelessness is a walk in a park (full of drug dealers)

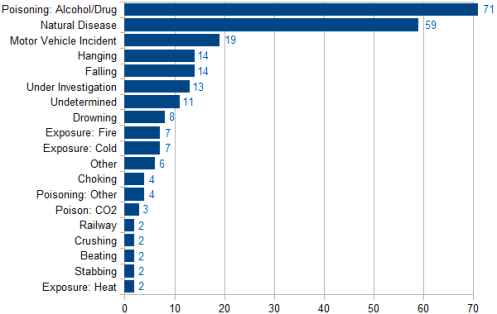

(Data from B.C. Coroners Service's Deaths among Homeless Individuals: 2007-2013)

The B.C. coroner’s report on homeless deaths between 2007 and 2013 separates the 250 deaths into 19 categories. The top two categories: Poisoning: Alcohol/Drugs (71) and Natural Causes (59) account for 130 deaths, over half of the total.

It’s true that far too many of the 250 deaths look preventable. But when I look at the breakdown by cause, I do not see homelessness killing people. I see drugs, disease and suicide as the real killers—and cars, of course. And the neglect of society.

Society could provide homeless people with easy round-the-clock access to positive and inclusive services that would help them be healthy, productive, contributing citizens but it chooses not to.

Instead, society shuns and stigmatizes homelessness and all but condones the 24-hour access to cheap street drugs that promise many homeless people a release from their despair and boredom.

The housing-first crowd would have us believe that health and well-being for homeless people begins and ends with giving a street person a social housing bedsit but I disagree. I believe that change needs to happen first at the street level and to the drug culture associated with homelessness or else the homeless drug addicts put in new social housing will simply bring the dangers of the street home with them.

If British Columbia was actually trying to accessorize its nascent U.S.-style drugs and homelessness situation with honest-to-goodness U.S.-style slums then I don’t think it could do better than it is—putting drug addicts on lifetime government disability, packing them into towers, giving them the key but otherwise throwing them away.

And now this brief word from my work ethic

I admit that it hasn’t worked for me so far but I still believe that in a market economy, the only sustainable path off the street is through a job.

If the B.C. government really is going to give drug addicts housing and pay for it for the rest of their lives, then I guess that could work but I don’t believe that the addicts themselves will ever work again and I have to ask how that is good for anyone?

As I’ve said before, I believe society has an interest in providing bridging services so homeless people can have the same 24-hour access to showers and laundry and storage that they would have if they weren’t homeless. This would give homeless people the freedom to take jobs and work whatever hours an employer wanted them to without them having to sacrifice their hygiene.

Last time I tried full-time employment, the hardest part of my job was trying to fit my hygiene needs into my employer’s work schedule.

I strongly approve of homeless prevention programs like the City of Vancouver’s Rent Bank—long overdue, But if someone cannot be prevented from becoming homeless, I believe it’s in society’s interests to be available immediately to help clear any obstacles to a homeless person continuing with their existing job or rejoining the workforce.

The way things are now, as long as I’m homeless, it’s easier and less stressful for me to not have a job and earn the money I do collecting returnable containers. That way I can control my hours.

You see, I’m the most understanding employer I know. I’ll happily give myself time off to go do laundry when the laundromats are open or go get shower during the window of opportunity when city facilities with accessible showers are open.

Homelessness without drugs like Wi without Fi

With every reduction in the supply and addiction to street drugs, I believe you would see a direct reduction in the dangers associated with homelessness.

If you could eliminate just three street drugs—heroin, cocaine and amphetamines (and their siblings: crack and crystal meth) from the equation, just imagine how that would transform being homeless.

Without addictions…

- You’re not nearly so forgetful so you don’t lose nearly so much stuff.

- You don’t stay up for days and then sleep like you’re in a coma so you’re not such easy prey for thieves.

- And there wouldn’t be nearly so many thieves to worry about.

- Also less paranoia and aggression to fuel violent outbursts.

- Not to mention less induced and aggravated mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolarity.

- Plus much less cumulative and irreversible neurological brain damage.

Street drugs are certainly not the only stumbling block to people living on the street but I see addiction as the biggest barrier that both faces homeless people and keeps society from seeing homelessness for what it really is; extreme poverty.

How can it stand to not have all its legs?

Remember harm reduction, prevention, treatment and enforcement? Whatever the hell happened to Vancouver’s four pillars strategy for dealing with drug addiction?

The harm reduction component is certainly visible and quite successful. The handing out of clean needles and crack pipes really does check the spread of transmittable diseases from sharing used drug paraphernalia and Vancouverites should be proud that no one using the Insite safe injection site in the Downtown Eastside has ever died from a drug overdose.

But where are the other three legs of the chair? Are they quietly working in the background; ridding our streets of drugs and drug dealers and encouraging and welcoming drug addicts into widely and easily available drug treatment programs?

I hope!

These days no one seems to talk about any part of the four pillars except harm reduction.

The authors of “Dying on the Streets” certainly don’t seem interested in prevention, treatment or enforcement and that’s a shame because I’m sure they know as well as anyone the enormous toll drug addiction takes on street people.

And that’s my problem with the report; it declares homelessness dangerous without ever quite saying why.

I see homelessness as dangerous like a toxic work environment that can be made safer by changing the culture. The Megaphone report instead implies that homelessness itself is dangerous like a live volcano or wire-walking across Niagara Falls (many have tried and died!).

I’ll take reports and people and governments seriously when they begin to get serious about facing up to the central role that street drugs and addiction play in the misery of homelessness.

In the meantime Megaphone magazine should be applauded for publishing the Dying on the Streets report.

It really is worth reading. It raises many good issues, calls for several sensible changes in the way statistics about homeless people are collected, and eloquently puts forward the authors’ belief that homelessness is the worst thing that can happen to a human being. It also has big colour photos and some heart-tugging stories that help put a necessary human face on homelessness.

And then, when you see a street corner vendors selling Megaphone magazine (the vendors are either on low incomes or homeless), consider buying a copy and making their life that little bit less awful.

Comments

8 Comments

Page Turner

Nov 9, 2014 at 7:17am

You absolutely do NOT give one mention to women, particularly with children, who are homeless because they "have done the right thing" and left an abusive relationship. MANY are not on drugs but looking for the only rooms in the lower mainland that are close in cost to their newly acquired( often facilitated by social workers so they can stay away from their abuser) welfare housing allowance.

Such an omission AND such an emphasis on the addicts on Hastings, which we hear about because we see them over and over again, feeds into the working public's frustration over welfare going to anyone on the DTES.

It did mine ... till I found myself in a transition house with a four month old infant after my tv exec husband locked me out of our Pt Grey home because "dinner was late and awful". He had a temper.

A big one. Many do. And they are not all addicts living in the slums. Nor are the wives who left them.

Stanley Q Woodvine

Nov 9, 2014 at 1:13pm

@Page

Hmph! The only time I refer to "men" or "women" is in specific context of statistical lifespan. Otherwise I deliberately refer to "people", which is shorter but synonymous with "human beings" which is what I mean.

First and foremost, this post is countering the assertions of a report that refused to acknowledge the glaring fact that drug and alcohol addictions were the most lethal factors in the deaths of the homeless people (over 85 percent men by the way) that the report was referring to.

If there is a bias in my post it is against drugs. I am writing from the perspective of a non-drug-addicted, non-social-assistance-collecting homeless individual.

I can only begin to write accurately about what I know.

Nothing that I've written takes away from anyone else's unique experience or precludes them from writing about them -- from their point of view -- just the way I do.

Sandra

Nov 9, 2014 at 5:18pm

But we need the homeless to be out there; otherwise how can we self righteously enlighten each other about how painfully compassionate we are.

bowser

Nov 11, 2014 at 1:46pm

Glad to see a homeless person who understands that drugs are the real problem. I do not agree with your statement that "society" is to blame for the drug problem. "Society" gives plenty of chances for a drug addict to change, but addicts prefer not to. That's a matter of PERSONAL CHOICE. Stanley, just as you CHOOSE to walk away from drugs, other CHOOSE to embrace drugs.

Stanley Q Woodvine

Nov 11, 2014 at 4:22pm

@bowser

Fair enough. I choose to walk away from drugs and many feel that the VPD choose to walk by DTES drug dealers in their haste to hand out jaywalking tickets.

The "choice" argument is weak in the face of addiction. If you're saying one strike in life (trying hard drugs and getting addicted) means that you're out and done for, I can only disagree.

This is akin to a doctor telling a person it was their own fault they picked up a water-borne parasite because they chose to go to Mexico and drink the water.

Society has a self interest to use its strength to help people get back on their feet when they fall.

If the people struggling in the water are too weak isn't it the human thing to help lift them out of the water and into the lifeboat?

If society doesn't have your back then what good is it?

And are you saying that A) society is incapable of stopping the trade in hard drugs and B)drug treatment doesn't work and thus C) the whole four pillars strategy was bullshit?

Sandra

Nov 12, 2014 at 12:40am

I don't know what Bowser thinks about the 4 pillars approach, but I don't think it's working and I surmise that from the amount of people that are still living the most inhumane version of life imaginable.

For Insite to work, all addicts would have to use it every single time they injected drugs, because that's the only way to keep them from accidentally overdosing behind the dumpster, or over at their buddy's place. They aren't going to use it every single time though, and they'll do their overdosing elsewhere, leaving Insite to crow about it's phony statistics.

The 4 pillars could have worked if it were being implemented 30 or 40 years ago when addictions meant heroin, not crystal meth. When the welfare rates were relatively higher and there was enough clean low cost housing and flop houses weren't as floppy as they are now. The numbers of heroin addicts were lower and addicts weren't competing with abandoned and dumped mental patients. Every now and then they would be forced into different residential rehab programs which worked for some and in the worst case scenario helped them clean up for a while and gave them a different perspective.

It's a welfare shell game now, and the uncountable number of people who have jobs working with drug addicts and the mentally would be on welfare themselves if we did the sensible thing and built secure medical facilities for them.

I don't see how centralizing the treatment and necessary ongoing care of people could come close to what we're spending now, including the increased security and policing we can expect now that we're labeling mental health patients acting out as terrorists.

Sandra

Nov 12, 2014 at 12:56am

Homeless in Vancouver can't be compared to homeless in Seattle or any other U.S. city. People in Canada never lost their homes due to criminal banking practices. I have no idea what draw or circumstance contributes to your life of homelessness, but you're the exception to the rule here and if we could find a proper place of residential care for the addicts and mentally ill, the SRO's wouldn't be so horrendously trashed and thrashed, leaving the poor and not sick room to breath and live.

Jay Eff

Nov 28, 2014 at 3:33pm

What happens to the corpses of the homeless? Are they buried or cremated? Who covers the costs?